In identifying the sets of invisible urban borders, we came to see the important role of personal experiences crossing borders, thresholds, divides in the city. Urban borders are not self-evident in the built environment as they are on maps. The boundaries become visible through personal experience, border stories reveal the hidden lines.

If invisible borders are revealed in personal narratives, what are some of the ways that we can find these stories and tease out the lines from the urban topography? We learned on Day 2 from one of our guest lecturers researching ethnic cafes, that we shouldn’t assume that ethnic minorities do not use the Internet or mobile technology. Today, we planned to compliment or replicate her investigation of ethnic communities at cafes by looking to see if personal narratives emerge on location-based social networks.

First, we narrowed down our list of urban border crossers. While everyone in the city crosses some kind of border in their daily life (administrative borders, life changes, infrastructure, social divides, control mechanisms), the urban border crossers we’re focusing on are those that have something at stake. The borders that are visible to them are invisible to others. This may be the result of their social background, economic condition, custom, or age group.

We decided to look for border stories and crossers in the posts, check-ins, and user profiles on Foursquare. Previous research by Philipp Kats at Strelka provides a sense of the relevancy of Foursquare in Moscow and a preliminary search of possible terms (an ethnic group or synonyms for “border”) were promising. Of course, we made sure to condition our assumptions: Foursquare cannot be taken as a representative or comprehensive indicator of the kinds of urban border crossers we’ve defined here. Many either do not have smartphones or use online social networks as a means of expression.

We examine spatial patterns among Moscow’s networked border crossers by: 1) identifying nodes and edges in those patterns; 2) extracting visual and verbal content to reconstruct spatial narratives; and 3) cataloging, aggregating, representing patterns.

First, we identify key minority groups and devise search terms using Foursquare, (including nationality, language, home cities, home vs border, passage, crossing; also consider searching using other languages). An example of this could be the word “border” in Russian. Many of the results returned by the search for “border” brought up the boundary between smokers and non-smokers in cafes and restaurants. While a clear, visible boundary is suggested by the choice between “smoking” and “non-smoking”, many of the tips left suggest that the border is indiscernible, unsubstantial, or simply: invisible.

In addition to using search terms to find border conditions at locations, we can look for specific institutions that service urban border crossers: cafes, transit hubs, courtyards, migration services. Once we’ve identified a location, we review tips, most liked tips, the check-in history of mayors and recent visitors.

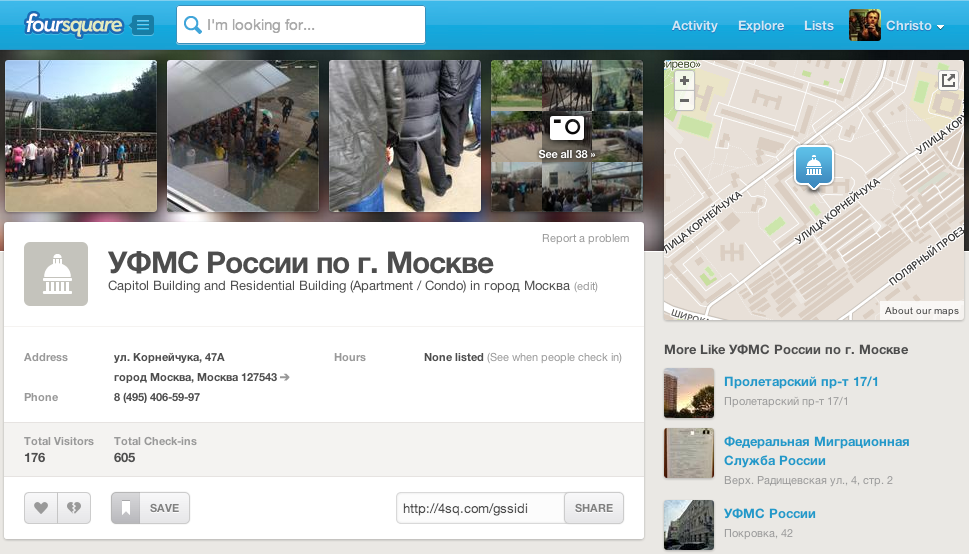

Sergei Rodionov’s story in The Village about his personal experience going through Federal Migration Services in Bibero includes a map of the locations he had to visit in and around the city on his way to a work permit. Many urban borders were crossed in the story. Is his the only story? We took the map and figured and identified the addresses and names of the various locations, inputting them into Foursquare.

The FMS center in Bibero is well documented on Foursquare. Over 600 check-ins by 175 unique visitors, people do not come here just once. The “mayor” (user with the most check-ins) logged 20 visits. For a government office, there were a lot of images posted. The images are of mostly of people in line. One image is of an identification card.

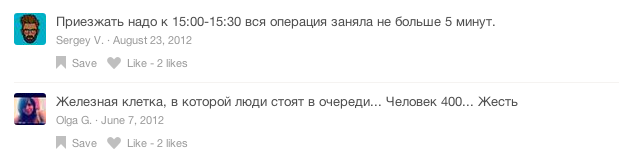

Unlike the story in The Village, the tips posted on Foursquare show the variety of the experiences with the work permit process. One user speaks of the best time to come – only 5 minutes in line between 3pm and 3:30pm. The next user decries the “iron cage” in which 400 people are crowded. And so the tips alternate.

From the individual experiences, we can drill down further into the spatial practices of the users. We can learn a lot about individual users: where they call home, what other locations they visit in the city, how they speak of their experiences in the city, and what activities they value. For user Tanya N. who shared her victory in gaining a work permit, we learn from her profile that she also frequents Kaluga – 2 hours east of Moscow – and Thailand.

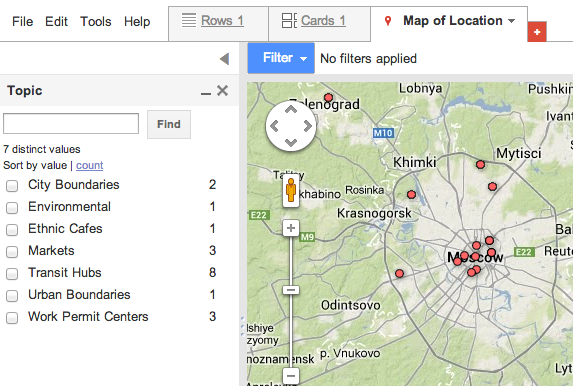

Interesting data like this is entered into a Google Fusion table. Here we can be quickly analyze and visualize the data on a map – filtering by topic or keyword.

Some of our preliminary research into urban border crossing stories on Foursquare led to several dead ends. The stories that emerged from transit hubs only spoke of the borders between commuters and bumzhis (Moscow’s homeless) or about the availability of wi-fi. But the investigation of places where work permit or migrant communities flow, exchange at the centers or markets – is still a fruitful direction to continue to pursue.